In the world of pastries, the art of lamination—the delicate layering of butter and dough in croissants—or the precision of French patisserie often steal the spotlight from cafés to bakeries.

Yet, in Southeast Asia, another tradition of artisanal sweets exists, equally, if not more, complex in its execution: Kueh.

Referred to by various names — kue, kuih, koay, gao, and gou — across Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, these traditional delicacies are a testament to a rich cultural heritage shaped by migration, indigenous ingredients, and diverse culinary techniques. The term kueh itself traces its origins to the Chinese character ‘糕’ or ‘粿,’ with its pronunciation varying across dialect groups .

Over the years of making kueh and discussing it with others, I’ve come to realise that despite its deep-rooted presence in Southeast Asian daily life, kueh is often dismissed as a humble street snack, overshadowed by the prestige of European pastries. One key reason is price — kueh remains highly affordable in wet markets compared to its European counterparts. However, this affordability is largely due to the dominance of mass production, which has shaped the market for decades. As a result, the artistry of traditional kueh-making has been taken for granted.

While it’s no surprise that fewer people take on the art of making kueh today, the reasons go beyond mere preference — it’s a craft that demands skill, patience, and an intimate understanding of technique.

Every step, from extracting coconut milk to carefully layering steamed batters, requires meticulous precision. Then there’s the sheer variety of ingredients involved, many of which are fresh, perishable, and require careful preparation. But the greatest challenge of all? Time. In a world where convenience dictates choices, the slow, deliberate process of crafting kueh from scratch has become a rare luxury — one that fewer people are willing to embrace.

ABOVE (Left) Equipment to press glutinous rice; (Right) My set-up to steam kueh.

With the rise of shortcuts and mass production, many Malaysians and Singaporeans have unknowingly grown accustomed to kueh that no longer reflect their original artistry. The delicate techniques of layering, steaming, fermenting, and hand-shaping — once second nature to generations past — are gradually fading from collective memory.

As factory-made versions flood the market, a generation is emerging that may not even realise what has been lost: the depth of flavour, the nuanced textures, and the cultural significance embedded in every carefully crafted bite.

To master the art of kueh-making requires not only precision but also an intuitive understanding of texture, layering, steaming, and the delicate interplay of flavours. If croissants are celebrated for their meticulous lamination, then surely, the beautifully threaded fine tunnels (ant’s nest in layman terms) of kueh ambon or the delicate wrapping of kueh dadar in thin pandan-crepes deserve equal admiration.

The Complexity of Kueh: More Than Meets the Eye

Unlike Western pastries, which largely rely on flour, butter, eggs, and sugar; kueh draws from a far broader spectrum of ingredients: glutinous rice, tapioca, coconut milk (santan), palm sugar (gula Melaka), and fragrant leaves like pandan. These ingredients are transformed using techniques that go beyond baking: steaming, boiling, frying, leaf-wrapping, and even fermentation.

The sheer variety of kuehs speaks to their technical depth:

- Kuih lapis, with its painstakingly steamed layers, requires careful timing to achieve its signature bouncy texture.

- Ang ku kueh (or kueh ku) demands precision in dough elasticity to encase its sweet mung bean or peanut filling without cracking. It can also be found in Southern China & Taiwan.

- Rempah udang involves a delicate balance between savoury and sweet, with glutinous rice encasing a spicy prawn filling, all wrapped in banana leaves and grilled to smoky perfection.

- Apam beras, a fermented rice cake, relies on natural yeast cultures to achieve its airy, sponge-like consistency.

ABOVE Angku Kueh (from left: Dragon Fruit Kueh Ku, Pandan Kueh Ku, Blue Pea & Red Dragon Fruit Kueh Ku)

Each kueh tells a story not only through its flavours but also through the craftsmanship required to perfect it—an artistry that has been passed down for generations, often through unwritten knowledge shared within families.

A Cultural Tapestry in Every Bite

Kuehs are more than just a breakfast snack or desserts; they are edible artifacts of history. Their presence spans across Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Peranakan cultures, each contributing unique variations.

The Peranakans, for instance, are known for vibrant, intricate kuehs such as kueh salat (also known as kueh seri muka by the Malay community)—a two-layered delicacy with pandan custard sitting atop glutinous rice, tinted blue with natural butterfly pea flower.

Meanwhile, Malay kuehs like ondeh-ondeh (glutinous rice balls filled with molten gula Melaka) highlight the influence of local palm sugar and coconut traditions.

These delicacies have been shaped by centuries of trade and migration, evolving through the exchange of ingredients, techniques, and cultural influences. The use of coconut milk and pandan embodies the essence of indigenous Southeast Asian flavours, while methods like steaming and layering draw parallels with oriental rice cakes.

Colonial encounters with the Portuguese and Dutch further introduced new adaptations, particularly in baking. It is plausible that kueh bahulu, the light and airy egg sponge cake, traces its origins to European madeleines, adapted over time to suit local tastes and ingredients.

Beyond their diverse origins, kuehs are deeply embedded in communal traditions. They are not just snacks but essential elements of cultural rituals, being served during weddings, festivals, and religious ceremonies. The making of kueh itself was once a communal act, with families gathering to shape, steam, and wrap these treats by hand, a practice that is slowly fading in the face of mass production.

Why Are Kuehs Less Celebrated Today?

Despite their intricate craftsmanship, kuehs do not command the same prestige as European pastries. One of the reason I realised is the shift in perception—many view them as inexpensive, everyday snacks rather than refined culinary creations. The absence of detailed documentation and formal training in kueh-making, unlike the rigorous schooling for French pastry chefs, has also contributed to their underappreciation.

Moreover, younger generations are often more familiar with croissants and éclairs than with serimuka or tepung pelita. European pastries have benefited from strong branding, sophisticated patisseries, and the allure of exclusivity, whereas kuehs remain largely confined to traditional markets and street stalls. It’s big time we change that.

Reframing Kueh as an Art Form

If the world can celebrate the delicate layering of puff pastry or the science behind choux dough, then why not the craftsmanship of kueh? A fresh perspective—one that views kuehs not just as nostalgic treats but as culinary artistry—could reposition them as refined, heritage-based pastries.

That said, I realise more modern chefs and kueh makers are beginning to reimagine kuehs, refining presentations while preserving the traditional integrity. Some fine patisseries have introduced kueh-inspired creations, incorporating gula Melaka into crème brûlée or infusing pandan into financiers. However, true appreciation comes not from fusion alone but from recognising kuehs for their own complexity and artistry.

I’d like to shoutout some of the kueh makers that I have been appreciating throughout the years—Dinesh (@myasiankitchen) and Gabriel Dominic (@gabdominic_kuehstry) for sharing their artisanal kuehs and their commitment for kueh making; as well as Pamelia Chia (@pameliachia) for her initiatives in documenting food culture and pushing the boundaries of tradition by experimenting with ingredients in new and exciting ways.

Educating the public on the techniques behind kueh-making—just as we do with croissants or mille-feuille—could restore their place as a respected craft. Whether through detailed storytelling, curated tasting experiences, or integrating them into contemporary café menus with thoughtful pairings, there is a need to elevate kuehs beyond their current perception.

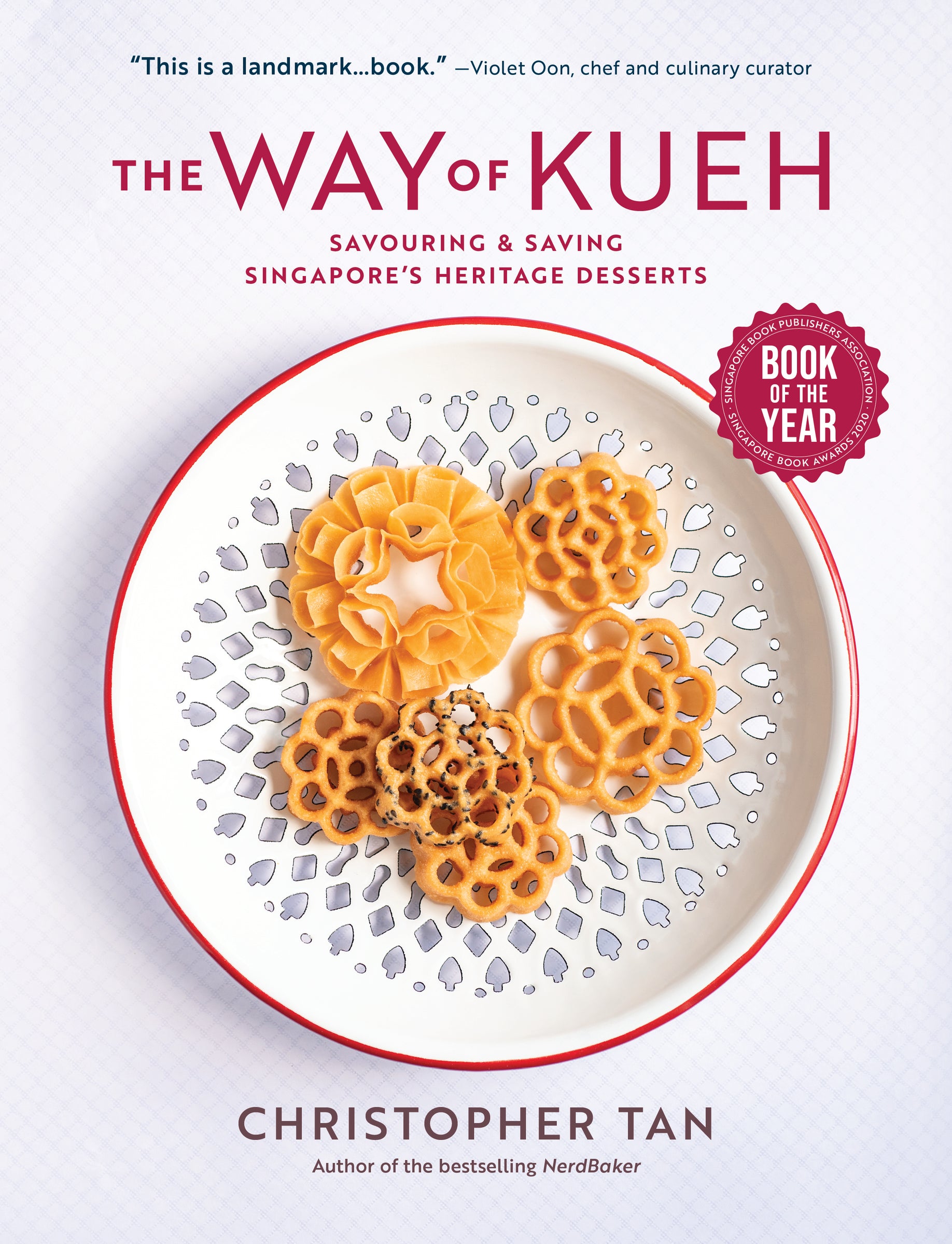

A book that I highly recommend for anyone who is curious in the world of kuehs is Christopher Tan’s The Way of Kueh. This book covers the various kuehs around the Nusantara region, he also explains the various kueh making techniques and stories, influence and history various kueh; and better yet, very intricate recipes of the kuehs he documented. This book is a true gem.

A Legacy Worth Preserving

Kuehs are more than just snacks — they are a testament to Southeast Asia’s culinary ingenuity. Their intricate textures, layered flavours, and deep-rooted cultural significance make them as deserving of admiration as the finest European pastries. But for them to regain their rightful place in the world of artisanal confections, they must be celebrated not just as nostalgic delicacies but as a sophisticated craft worth preserving and elevating.

It’s time we looked beyond the croissant and gave kuehs the recognition they truly deserve.

Leave a comment